Zoom on PHP objects and classes (PHP 5)

PHP objects introduction

Everybody uses objects nowadays. Something that was not that easy to bet on when PHP 5 got released 10 years ago (2005).

I still remember this day, I wasn't involved in internals code yet, so I didn't know much things about how all this big machine

could work. But I had to note at this time, when using this new release of the language, that jumps had been made compared to old

PHP 4.

The major point advanced for PHP 5 adoption was : "it has a new very powerful object model". That wasn't lies.

Today, 10 years later, something like 90% of the PHP source code involving objects haven't changed since PHP 5.0.

That shows how resulted this object model was when released. Sure it got improved through time, with new features especially.

Here, I will show you as usual how all this stuff works internally. The goal is always the same : you understand and master

what happens in the low level, to make a better usage of the language everyday.

Also, I will show you how memory usage has been really worked hard about objects, and how objects are nice about memory, compared

to equivalent arrays (when possible).

We will focus on PHP 5, starting with PHP 5.4, for this article. The statements will be true for 5.5 and 5.6, which have changed

nearly nothing in object model internals. This is not the case of PHP 5.3, which has a less resulted object model, nice improvements (both in term of user features, and general performances) were added back in PHP 5.4.

About PHP 7, the object model has not been reworked deeply, only tidy up things on

surface. Why ? Because we don't need to : it works. Of course, userland features were added but here we don't care about those : only the

internal design (the truth) scores :-)

Starter example

Ok so let's start with some synthetic benchmarks to demonstrate things :

class Foo {

public $a = "foobarstring";

public $b;

public $c = ['some', 'values'];

}

for ($i=0; $i<1000; $i++) {

$m = memory_get_usage();

${'var'.$i} = new Foo;

echo memory_get_usage() - $m"\n";

}

This code declares a simple 3 attributes class, and then in a loop, it creates 1000 objects of this class, showing the memory usage diff

between allocations.

That are 262 bytes diff at every object creation (LP64). Creating an object of class Foo, plus creating a PHP variable to store the object into it, allocate 262 bytes in PHP's heap memory (LP64).

Let's try now to turn this object into an equivalent array, some kind of :

for ($i=0; $i<1000; $i++) {

$m = memory_get_usage();

${'var'.$i} = [['some', 'values'], null, 'foobarstring'];

echo memory_get_usage() - $m . "\n";

}

The array embeds the same values : an array, a null and a foobar string.

The difference between arrays creation is 1160 bytes (LP64) : that is something like 4 to 5 times more memory eaten.

Let's do another quick bench :

$class = <<<'CL'

class Foo {

public $a = "foobarstring";

public $b;

public $c = ['some', 'values'];

}

CL;

echo memory_get_usage() . "\n";

eval($class);

echo memory_get_usage() . "\n";

As class declaration is honorred at compile time, we use an eval() statement to declare it at runtime and measure - with the PHP memory manager - its memory usage - just for it - we haven't created any object of it in this code (yet).

The diff memory is 2216 bytes, aka about 2Kb (assuming LP64).

Now, we are going to dive into PHP's sources to show you what happens, and to confirm our practice by some theory.

It all begins with a class...

A class is represented internally by the zend_class_entry structure. Here it is :

struct _zend_class_entry {

char type;

const char *name;

zend_uint name_length;

struct _zend_class_entry *parent;

int refcount;

zend_uint ce_flags;

HashTable function_table;

HashTable properties_info;

zval **default_properties_table;

zval **default_static_members_table;

zval **static_members_table;

HashTable constants_table;

int default_properties_count;

int default_static_members_count;

union _zend_function *constructor;

union _zend_function *destructor;

union _zend_function *clone;

union _zend_function *__get;

union _zend_function *__set;

union _zend_function *__unset;

union _zend_function *__isset;

union _zend_function *__call;

union _zend_function *__callstatic;

union _zend_function *__tostring;

union _zend_function *serialize_func;

union _zend_function *unserialize_func;

zend_class_iterator_funcs iterator_funcs;

/* handlers */

zend_object_value (*create_object)(zend_class_entry *class_type TSRMLS_DC);

zend_object_iterator *(*get_iterator)(zend_class_entry *ce, zval *object, int by_ref TSRMLS_DC);

int (*interface_gets_implemented)(zend_class_entry *iface, zend_class_entry *class_type TSRMLS_DC); /* a class implements this interface */

union _zend_function *(*get_static_method)(zend_class_entry *ce, char* method, int method_len TSRMLS_DC);

/* serializer callbacks */

int (*serialize)(zval *object, unsigned char **buffer, zend_uint *buf_len, zend_serialize_data *data TSRMLS_DC);

int (*unserialize)(zval **object, zend_class_entry *ce, const unsigned char *buf, zend_uint buf_len, zend_unserialize_data *data TSRMLS_DC);

zend_class_entry **interfaces;

zend_uint num_interfaces;

zend_class_entry **traits;

zend_uint num_traits;

zend_trait_alias **trait_aliases;

zend_trait_precedence **trait_precedences;

union {

struct {

const char *filename;

zend_uint line_start;

zend_uint line_end;

const char *doc_comment;

zend_uint doc_comment_len;

} user;

struct {

const struct _zend_function_entry *builtin_functions;

struct _zend_module_entry *module;

} internal;

} info;

};

Huge isn't it ? Its size, assuming an LP64 platform, is 568 bytes.

Everytime PHP needs to declare a class, it must allocate a zend_class_entry, and that will raise its memory heap usage of barely half a kilobyte, just for the class structure, not talking about everything behind it.

And of course that is not finished, because like you can see, this zend_class_entry structure is full of pointers, that need to be allocated.

The first thing one may remember is that a PHP class (not a PHP object), is a "heavy" thing to store in memory.

In fact, classes are much more heavy in memory that related future objects to create from it.

Also, a class is not alone : it declares attributes (static or not, whatever), methods and constants.

Those will consume memory as well. For methods, the computation is not really easy to make, but obviously, the bigger the method body, the more memory this method will eat, because the bigger its OPArray will be. Also, static variables declared into a method (if any) will eat memory.

Internally a method is strictly the same as a function, there is no difference in term of performance or memory usage in both.

Then come the attributes. Those later will also allocate memory, depending on their default values : an integer will be light, but a big static array will eat more memory.

There is a last thing to take care of, which is detailed into the zend_class_entry source code as well : PHP comments.

PHP comments, also known as annotations, are strings, in C : char * buffers, and they need to be allocated and are really easy to compute, as in C not using Unicode like PHP does : one character = one byte. For more information about how PHP manages strings internally, please read the dedicated article.

The more annotations you have in your class, the more memory will be eaten when the class is created (parsed). Same thing for methods or attributes.

The doc_comment field is used and retains the class annotations. For methods : their structure also has a doc_comment field, and same for attributes.

User classes VS internal classes

Everybody spotted it : a user class is a class defined using PHP, an internal class in a class defined hacking PHP's source, or provided by any extension.

The biggest difference to know, is that user classes allocate request-bound memory whereas internal classes allocate "permanent" memory

That means that when PHP finishes to treat the actual web HTTP request, it will deallocate and destroy every user classes it knows, to leave the room blank for the next request. This is known as the share nothing architecture, this is how PHP has been designed since the begining, and there is no plan to change it.

So everytime you start a request and make PHP parse classes : it allocates memory for your class. Then you use your class, and then PHP destroys everything about it.

So you really should be sure to use every class you declared, if not : you are wasting memory.

Use an autoloader, because autoloaders delay class parsing/declaration at runtime, when PHP really needs the dedicated class.

An autoloader will slow down runtime, but will be smart about your process memory usage, as it will not be triggered if the class is not actually really used.

This is not the case at all for internal classes : their memory is allocated permanently, weither or not they will ever be used, and they will only be destroyed when PHP itself will die : when it has finished treating the number of requests you asked it for (assuming web SAPI, like PHP-FPM f.e), usually, a PHP web worker treats several thousands of requests before dying.

That's a point why internal classes are more performant than user classes. (Only static attributes will be destroyed at the end of every request, nothing more).

if (EG(full_tables_cleanup)) {

zend_hash_reverse_apply(EG(function_table), (apply_func_t) clean_non_persistent_function_full TSRMLS_CC);

zend_hash_reverse_apply(EG(class_table), (apply_func_t) clean_non_persistent_class_full TSRMLS_CC);

} else {

zend_hash_reverse_apply(EG(function_table), (apply_func_t) clean_non_persistent_function TSRMLS_CC);

zend_hash_reverse_apply(EG(class_table), (apply_func_t) clean_non_persistent_class TSRMLS_CC);

}

static int clean_non_persistent_class(zend_class_entry **ce TSRMLS_DC)

{

return ((*ce)->type == ZEND_INTERNAL_CLASS) ? ZEND_HASH_APPLY_STOP : ZEND_HASH_APPLY_REMOVE;

}

Note that even with an OPCode cache, like OPCache, class creation and destruction still happen at every request for user declared classes. OPCache only speeds up those two steps.

Internal class are more performant than user declared classes, just by the fact that they get allocated only once for all, whereas userland declared classes need to be destroyed and reloaded at every request. Internal classes also got many possibilities not available to user classes.

So you have noted, if you activate many PHP extensions that each declare many classes, but you just use a small part of them : you are wasting memory as well.

Remember that PHP extensions declare their classes at the time PHP starts, even if in later requests to come those classes will not be used.

That's why we usually tell users to not keep enabled PHP extensions they just don't use : that's a pure memory waste, especially if the extension declares many classes (among other things extension may allocate as well).

Classes, interfaces or traits are all the same

PHP uses the same zend_class_entry structure internally to manage PHP classes, PHP interfaces and PHP traits.

So everytime you declare an interface or a trait, the zend_class_entry will be used as well.

Internally, PHP classes, interfaces and traits are managed by the exact same structure : zend_class_entry

And as you've seen, the structure is heavy.

Sometimes in code, users declare interfaces to be able to use their name in PHP catch blocks. That allows them to catch one kind of exception only.

Something like this :

interface BarException { }

class MyException extends Exception implements BarException { }

try {

$foo->bar():

} catch (BarException $e) { }

What is pitty here, is that nearly one kilobyte is used, just to declare the BarException interface. Exactly 912 bytes (LP64) :

$class = <<<'CL'

interface Bar { }

CL;

$m = memory_get_usage();

eval($class);

echo memory_get_usage() - $m . "\n"; /* 912 bytes */

I'm not telling it is bad, nor silly, I'm not blaming anyone nor anything. I just show you facts you perhaps were not aware of.

So remember, internally, classes and interfaces (and traits), are exactly used the same way. Simply, an interface will not be able to be added attributes, the PHP parser or compiler will forbid this to you, but the zend_class_entry structure is still used, just that its static_members_table and other fields will not be allocated pointers, that's all.

Declaring a class or an equivalent trait or equivalent interface, will barely use the same memory amount, as internally, those 3 concepts share the same structure.

Class binding

Class binding is a hidden thing PHP users are usually not aware of, until they wonder how things work.

This concept is yet really important to understand, we could define it as "the process that prepares a class and every piece of related data for it to be fully usable by the PHP user".

This process is very easy and cheap when we talk about a single class, that is a class not extending anyone, not using any trait, and not implementing any interface. The binding process for such class will be entirely done at compile time, that means that it will be very optimized and won't consume some PHP runtime.

Please, notice here that we're interested in the user-declared-class binding process. For internal classes, the same process is done when the classes are registered by PHP Core or PHP extensions, this happens very soon before the user scripts are run, and this happens only once in PHP lifetime, thus the userland runtime never suffers from that in term of performance.

Binding a single class is entirely done at compile time. On this point, performances tend to reach internal classes'.

Things become much more complicated when we talk about interfaces implementations, or class inheritance.

In such case, class binding will mainly copy every thing of interest from the parent to the child, would both be classes or interfaces. Let's see that :

/* Single class */

case ZEND_DECLARE_CLASS:

if (do_bind_class(CG(active_op_array), opline, CG(class_table), 1 TSRMLS_CC) == NULL) {

return;

}

table = CG(class_table);

break;

In case of a simple class declaration, we run do_bind_class(). This function just registers the already-fully-defined class into the class table for further use at runtime, and performs checks about eventual abstract methods into it, like this :

void zend_verify_abstract_class(zend_class_entry *ce TSRMLS_DC)

{

zend_abstract_info ai;

if ((ce->ce_flags & ZEND_ACC_IMPLICIT_ABSTRACT_CLASS) && !(ce->ce_flags & ZEND_ACC_EXPLICIT_ABSTRACT_CLASS)) {

memset(&ai, 0, sizeof(ai));

zend_hash_apply_with_argument(&ce->function_table, (apply_func_arg_t) zend_verify_abstract_class_function, &ai TSRMLS_CC);

if (ai.cnt) {

zend_error(E_ERROR, "Class %s contains %d abstract method%s and must therefore be declared abstract or implement the remaining methods (" MAX_ABSTRACT_INFO_FMT MAX_ABSTRACT_INFO_FMT MAX_ABSTRACT_INFO_FMT ")",

ce->name, ai.cnt,

ai.cnt > 1 ? "s" : "",

DISPLAY_ABSTRACT_FN(0),

DISPLAY_ABSTRACT_FN(1),

DISPLAY_ABSTRACT_FN(2)

);

}

}

}

Nothing to add, that was the easy case.

Now, things become more complicated about interface implementation, here are the task needed to be done to bind a class implementing an interface :

- Check if the interface is not already implemented

- Check if the class that wants to implement the interface, is actually a class, and not an interface itself (remember that both are treated the same)

- Copy the constants from interface into the class, checking possible collisions

- Copy the methods from the interface into the class

- Checking for possible collisions

- Checking mismatch in declaration (turning an interface method into static in child class, f.e)

- Add the interface and all its possible mother interfaces to the interface list the class implements

But take care, when we say "copy", this is not a full deep copy, constants, attributes and functions are all refcounted : the refcount is just incremented by one, meaning one more entity into memory is using the item.

Binding a class, is barely copying every constant/attributes/methods from its parent, and its interfaces into the current class body - while performing checks.

The class needs to be fully resolved and ready for use at runtime.

Constants, attributes and functions are all refcounted, no real copies take place, but the binding process is still not a light step in terms of performance.

ZEND_API void zend_do_implement_interface(zend_class_entry *ce, zend_class_entry *iface TSRMLS_DC)

{

/* ... ... */

} else {

if (ce->num_interfaces >= current_iface_num) { /* resize the vector if needed */

if (ce->type == ZEND_INTERNAL_CLASS) {

ce->interfaces = (zend_class_entry **) realloc(ce->interfaces, sizeof(zend_class_entry *) * (++current_iface_num));

} else {

ce->interfaces = (zend_class_entry **) erealloc(ce->interfaces, sizeof(zend_class_entry *) * (++current_iface_num));

}

}

ce->interfaces[ce->num_interfaces++] = iface; /* Add the interface to the class */

/* Copy every constants from the interface constants table to the current class constants table */

zend_hash_merge_ex(&ce->constants_table, &iface->constants_table, (copy_ctor_func_t) zval_add_ref, sizeof(zval *), (merge_checker_func_t) do_inherit_constant_check, iface);

/* Copy every methods from the interface methods table to the current class methods table */

zend_hash_merge_ex(&ce->function_table, &iface->function_table, (copy_ctor_func_t) do_inherit_method, sizeof(zend_function), (merge_checker_func_t) do_inherit_method_check, ce);

do_implement_interface(ce, iface TSRMLS_CC);

zend_do_inherit_interfaces(ce, iface TSRMLS_CC);

}

}

Notice the difference between internal classes and user ones ? The former will use realloc() to allocate memory, while the later will use erealloc(). Like I said : realloc() will allocate "permanent" memory, whereas erealloc() will allocate "request-bound" memory.

So, you can see that when the two constant tables are merged (the interface one and the class one), zval_add_ref is used as merge callback : it will not copy the constant from one table to another, but share its pointer just adding a refcount.

For the functions tables (methods), do_inherit_method is run for any of them. Here it is :

static void do_inherit_method(zend_function *function)

{

function_add_ref(function);

}

ZEND_API void function_add_ref(zend_function *function)

{

if (function->type == ZEND_USER_FUNCTION) {

zend_op_array *op_array = &function->op_array;

(*op_array->refcount)++;

if (op_array->static_variables) {

HashTable *static_variables = op_array->static_variables;

zval *tmp_zval;

ALLOC_HASHTABLE(op_array->static_variables);

zend_hash_init(op_array->static_variables, zend_hash_num_elements(static_variables), NULL, ZVAL_PTR_DTOR, 0);

zend_hash_copy(op_array->static_variables, static_variables, (copy_ctor_func_t) zval_add_ref, (void *) &tmp_zval, sizeof(zval *));

}

op_array->run_time_cache = NULL;

}

}

The function's OPArray is added a refcount, and every possible static variables declared in the function (which here is a method) is also copied, again also using zval_add_ref.

Thus, the overall copy process is heavy in term of CPU because it involves many loops and checks, but in term of memory usage, we are really kind here.

Unfortunately, the interface binding is nowadays fully delayed at runtime, and you will suffer from it at every request.

When it comes to talk about inheritance, well the process is barely the same as interface implementation, thus it is even more complicated because it involves more stuff.

What is interesting to note however, is that the binding is done at compile time if PHP already knows about the class, and in runtime for the opposite case

The inheritance binding is done at compile time if PHP already knows the parent class, and in runtime for the opposite case.

So you'd better declare things like this :

/* good */

class A { }

class B extends A { }

Instead of :

/* bad */

class B extends A { }

class A { }

If you use an autoloader and one-class-per-file rule, PHP will likely never known one class' ancestors when it comes to parse it, and thus, will delay the class binding at runtime.

Class binding routine can even lead to very strange behaviors, like :

/* this code snippet works */

class B extends A { }

class A { }

/* this code snippet doesn't work :

Fatal error: Class 'B' not found */

class C extends B { }

class B extends A { }

class A { }

I already explained such a case in another article.

In case one, the binding of class B is delayed at runtime, because when the compiler reaches the class B declaration, it knows nothing about A yet. When runtime fires, it binds the class to A and it finds A, because the compiler compiled A, as A is a single class, the compiler could take care of it entirely.

In case two, things are different. The binding of C is delayed at runtime, because the compiler knows nothing about B when it tries to compile B.

But when the runtime fires to bind C, it looks for B, which doesn't exist, because the compiler couldn't compile it neither, as B itself extends someone. "Class B doesn't exist" , end of story.

...then come objects

Ok, now you know several statements :

- Classes are heavy items in memory

- Internal classes are more optimized than user classes, because those latter will need to be created/destroyed at every request, internal classes are permanent.

- Classes, interfaces or traits use the exact same structure and same procedures, very little differences

- When doing inheritance or implementations, the binding process is heavy and long for CPU, but light about memory usage as many things are shared and not duplicated. Also, you'd better have class binding fire at compile time

Now let's talk about our objects.

Our first chapter showed the creation of a "classical" object from a "classical" user class (that is : there is nothing special in there), the object creation was very light in term of memory, something like a ridiculous amount of 200 bytes on LP64 platform.

This, is because of the class.

The class itself has been compiled, and this latter eats memory; but that's for the good : this is to make every single object eat less memory.

An object is in fact a ridiculously tiny set of tiny structures.

Object methods management

Reminder: Methods and functions are exactly the same into the engine : a zend_function structure (union). This is just vocabulary, and the fact that methods are the only place where

$thiscan be used.

Methods are represented by an union (zend_function). Methods are compiled by the PHP compiler, and added to the function_table attribute of the zend_class_entry. So at runtime every method is present, this is just a matter of fetching back its pointer to execute it.

typedef union _zend_function {

zend_uchar type;

struct {

zend_uchar type;

const char *function_name;

zend_class_entry *scope;

zend_uint fn_flags;

union _zend_function *prototype;

zend_uint num_args;

zend_uint required_num_args;

zend_arg_info *arg_info;

} common;

zend_op_array op_array;

zend_internal_function internal_function;

} zend_function;

When an object tries to invoke a method, the engine will by default lookup into the object's class function table to invoke it, and if the method doesn't exist, it will invoke the magic __call(). It will also check visibility (public/protected/private), and act accordingly :

static union _zend_function *zend_std_get_method(zval **object_ptr, char *method_name, int method_len, const zend_literal *key TSRMLS_DC)

{

zend_function *fbc;

zval *object = *object_ptr;

zend_object *zobj = Z_OBJ_P(object);

ulong hash_value;

char *lc_method_name;

ALLOCA_FLAG(use_heap)

if (EXPECTED(key != NULL)) {

lc_method_name = Z_STRVAL(key->constant);

hash_value = key->hash_value;

} else {

lc_method_name = do_alloca(method_len+1, use_heap);

zend_str_tolower_copy(lc_method_name, method_name, method_len);

hash_value = zend_hash_func(lc_method_name, method_len+1);

}

/* If the method is not found */

if (UNEXPECTED(zend_hash_quick_find(&zobj->ce->function_table, lc_method_name, method_len+1, hash_value, (void **)&fbc) == FAILURE)) {

if (UNEXPECTED(!key)) {

free_alloca(lc_method_name, use_heap);

}

if (zobj->ce->__call) { /* if the class has got a __call() handler */

return zend_get_user_call_function(zobj->ce, method_name, method_len); /* call the __call() handler */

} else {

return NULL; /* else return NULL, which will likely lead to a fatal error : method not found */

}

}

/* Check access level */

if (fbc->op_array.fn_flags & ZEND_ACC_PRIVATE) {

zend_function *updated_fbc;

updated_fbc = zend_check_private_int(fbc, Z_OBJ_HANDLER_P(object, get_class_entry)(object TSRMLS_CC), lc_method_name, method_len, hash_value TSRMLS_CC);

if (EXPECTED(updated_fbc != NULL)) {

fbc = updated_fbc;

} else {

if (zobj->ce->__call) {

fbc = zend_get_user_call_function(zobj->ce, method_name, method_len);

} else {

zend_error_noreturn(E_ERROR, "Call to %s method %s::%s() from context '%s'", zend_visibility_string(fbc->common.fn_flags), ZEND_FN_SCOPE_NAME(fbc), method_name, EG(scope) ? EG(scope)->name : "");

}

}

} else {

/* ... ... */

}

You may spot an interesting thing, look at the first lines :

if (EXPECTED(key != NULL)) {

lc_method_name = Z_STRVAL(key->constant);

hash_value = key->hash_value;

} else {

lc_method_name = do_alloca(method_len+1, use_heap);

/* Create a zend_copy_str_tolower(dest, src, src_length); */

zend_str_tolower_copy(lc_method_name, method_name, method_len);

hash_value = zend_hash_func(lc_method_name, method_len+1);

}

This is PHP case insensibility. PHP must turn every function to lowercase (zend_str_tolower_copy()), before calling it. This is not a heavy step, but it can seem pretty wasteful, considering it must happen for every method call for every class. This will burn some more CPU cycles for nothing really usefull, and you'd better prevent it.

Look carefully at the code, there is an if statement. The key variable prevents the code from running the case lowering function (the else part), and this key is an optimization that has been added starting from PHP 5.4. If the method call is not dynamic, the compiler has already computed the key, and the runtime will have less job to do.

class Foo { public function BAR() { } }

$a = new Foo;

$b = 'bar';

$a->bar(); /* static call : good */

$a->$b(); /* dynamic call : bad */

When the compiler compiles a function/method, it immediately lowercases it. The above function BAR() is turned into bar() by the compiler, when it adds the method to the class function table.

The compiler turns every function/method name to lowercase when it compiles it. PHP really is case-insensible when we talk about functions/methods.

When the method call happens, on the example above, the first call is static : the compiler have computed the key for the string "bar", and then when it comes to run the method call, it has less job to do.

The second call above however, is dynamic; the compiler knows nothing about "$b" : it can't compute a key for the method call, we will then fall into the else case at runtime, and we will have to both turn the string to lowercase, and to compute its hash (zend_hash_func()) at runtime, which is not especially what you're looking for if we talk about performances.

About __call(), it is not that bad about performances, there is however more work to do than calling an existing function though.

Object attributes management

Here is what happens :

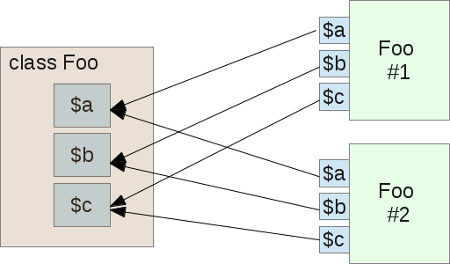

As you can see, when you create several objects of the same class, the engine will make every attribute point on the same pointer as the one defined into the class attributes.

The class stores the attributes, not only its own static attributes - but also objects ones - for the life of the class : forever for internal classes, request bound lifetime for user classes. Creating an object does not involve creating its attributes, thus, that's a fast and memory saver approach.

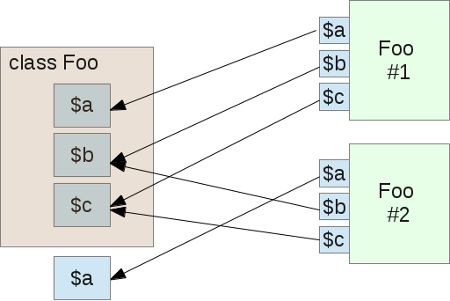

Only at the time an object is going to change one of its attribute, the engine will create a new one and affect it, assuming you change the $a attribute on the object Foo #2 :

So creating an object, is in fact "just" creating a zend_object structure, which weight 32 bytes under LP64...

typedef struct _zend_object {

zend_class_entry *ce;

HashTable *properties;

zval **properties_table;

HashTable *guards; /* protects from __get/__set ... recursion */

} zend_object;

...add this new zend_object to the object store. The object store is a zend_object_store structure : it is the global Zend Engine registry of objects, the place where in every object is stored exactly once :

ZEND_API zend_object_value zend_objects_new(zend_object **object, zend_class_entry *class_type TSRMLS_DC)

{

zend_object_value retval;

*object = emalloc(sizeof(zend_object));

(*object)->ce = class_type;

(*object)->properties = NULL;

(*object)->properties_table = NULL;

(*object)->guards = NULL;

/* Add the object into the store */

retval.handle = zend_objects_store_put(*object, (zend_objects_store_dtor_t) zend_objects_destroy_object, (zend_objects_free_object_storage_t) zend_objects_free_object_storage, NULL TSRMLS_CC);

retval.handlers = &std_object_handlers;

return retval;

}

Then, the engine creates the properties vector of our object :

ZEND_API void object_properties_init(zend_object *object, zend_class_entry *class_type)

{

int i;

if (class_type->default_properties_count) {

object->properties_table = emalloc(sizeof(zval*) * class_type->default_properties_count);

for (i = 0; i < class_type->default_properties_count; i++) {

object->properties_table[i] = class_type->default_properties_table[i];

if (class_type->default_properties_table[i]) {

#if ZTS

ALLOC_ZVAL( object->properties_table[i]);

MAKE_COPY_ZVAL(&class_type->default_properties_table[i], object->properties_table[i]);

#else

Z_ADDREF_P(object->properties_table[i]);

#endif

}

}

object->properties = NULL;

}

}

Like you can see, we allocate a pure C table/vector of zval* based on the object's class declared properties, and, in case of non thread safe PHP, we just add a refcount to the property, whereas using Zend thread safety (ZTS), we must deeply copy the zval.

That's one of the numerous point that confirms that ZTS mode is slower and more resource user than a non ZTS PHP.

PHP running with ZendThreadSafety activated (ZTS) is both slower and less memory friendly than a non-ZTS PHP.

Now you wonder two things :

- What's the difference bewteen properties_table and properties in the zend_object structure ?

- If we affected our object's attributes in a C vector, how will we fetch them back ? Browse the vector every time ? (counter-performant)

The answer to both those questions relies in a clever trick : zend_property_info.

Here is zend_property_info :

typedef struct _zend_property_info {

zend_uint flags;

const char *name;

int name_length;

ulong h;

int offset;

const char *doc_comment;

int doc_comment_len;

zend_class_entry *ce;

} zend_property_info;

Every declared attribute(property) of an object has a corresponding property info that has been added to its zend_class_entry, into the property_info field. The compiler created this when it compiled the declared attributes in the class :

class Foo

{

public $a = 'foo';

protected $b;

private $c;

}

struct _zend_class_entry {

/* ... ... */

HashTable function_table;

HashTable properties_info; /* here are the properties infos about $a, $b and $c */

zval **default_properties_table; /* and here, we'll find $a, $b and $c with their default values */

int default_properties_count; /* this will have the value of 3 : 3 properties */

/* ... ... */

The properties_infos is a table that will both tell the object if the attribute it asks access for exists, and if it exists, what is its index number in the object->properties pure C array. Clever and fast way of accessing attributes.

If the attribute doesn't exist, and if we try to write into it : we try to call __set() if possible, if not, we create a dynamic attribute, and this one will be stored into object->property_table field. If the attribute exists, we then check the visibility and scope access (public/protected/private).

property_info = zend_get_property_info_quick(zobj->ce, member, (zobj->ce->__set != NULL), key TSRMLS_CC);

if (EXPECTED(property_info != NULL) &&

((EXPECTED((property_info->flags & ZEND_ACC_STATIC) == 0) &&

property_info->offset >= 0) ?

(zobj->properties ?

((variable_ptr = (zval**)zobj->properties_table[property_info->offset]) != NULL) :

(*(variable_ptr = &zobj->properties_table[property_info->offset]) != NULL)) :

(EXPECTED(zobj->properties != NULL) &&

EXPECTED(zend_hash_quick_find(zobj->properties, property_info->name, property_info->name_length+1, property_info->h, (void **) &variable_ptr) == SUCCESS)))) {

/* ... ... */

} else {

zend_guard *guard = NULL;

if (zobj->ce->__set && /* class has a __set() ? */

zend_get_property_guard(zobj, property_info, member, &guard) == SUCCESS &&

!guard->in_set) {

Z_ADDREF_P(object);

if (PZVAL_IS_REF(object)) {

SEPARATE_ZVAL(&object);

}

guard->in_set = 1; /* prevent circular setting */

if (zend_std_call_setter(object, member, value TSRMLS_CC) != SUCCESS) { /* call __set() */

}

guard->in_set = 0;

zval_ptr_dtor(&object);

/* ... ... */

So, until you write to your object, its memory consumption will not vary. When you write to it, you start making it bigger, as it will retain the attributes you wrote into it, until it dies. Methods do not consume any memory related to the object, but they belong to the class.

Objects acting as references, thanks to the object store

Objects are not references. I demonstrate it in a small script :

function foo($var) {

$var = 42;

}

$o = new MyClass;

foo($o);

var_dump($o); /* this is still an object, not the integer 42 */

Everybody says that "objects are references in PHP 5", even the official manual sometimes suggests this ;-) This is horribly wrong technically.

However, objects borrow references behavior, as when you pass a variable which is an object to a function, this function can modify the same object.

Objects are not passed by references, this is wrong. However, they borrow the same behavior as PHP variables references.

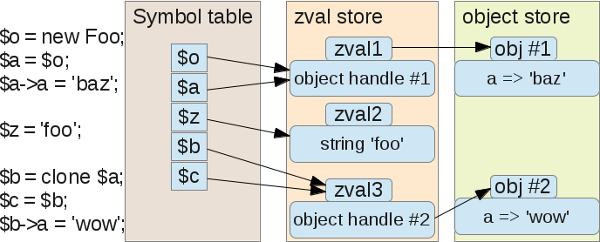

This is because in the zval you pass to the function, you don't pass an object precisely, but its unique identifier, that will serve to look it up into the global object store, thus effectively leading to the same object at the end.

You can end up having 3 different zvals in memory, they can all store into them the same object handle, and then they will lead to the same object into memory.

object(MyClass)#1 (0) { } /* #1 is the object handle (number), it is unique */

So you carry in your variables the same object handle, and then it will lead to the same object.

The zend_object_store takes care of memorizing objects only once in memory. The only way to write into the store, is to create a new object, weither with the new keyword, the unserialize() function, the reflection API or the clone keyword. Every other operation will never duplicate or create a new object into the store.

typedef struct _zend_objects_store {

zend_object_store_bucket *object_buckets;

zend_uint top;

zend_uint size;

int free_list_head;

} zend_objects_store;

typedef struct _zend_object_store_bucket {

zend_bool destructor_called;

zend_bool valid;

zend_uchar apply_count;

union _store_bucket {

struct _store_object {

void *object;

zend_objects_store_dtor_t dtor;

zend_objects_free_object_storage_t free_storage;

zend_objects_store_clone_t clone;

const zend_object_handlers *handlers;

zend_uint refcount;

gc_root_buffer *buffered;

} obj;

struct {

int next;

} free_list;

} bucket;

} zend_object_store_bucket;

What is $this ?

You know $this from PHP. Internally, $this is not very complex to understand, but there is code related to it in several parts of the engine, in fact, at every needed stage : at compile time, in execution time variable fetching code, etc...

As $this is "magical", appears and disappears when it has to, automaticaly owns the current object, then that means that internal code to manage $this does everything for you. Let's have a look.

First, the compiler will forbid you to write to $this. For that, it checks every assignation you try to do, and if you assign $this, you'll generate a fatal error.

/* ... ... */

if (opline_is_fetch_this(last_op TSRMLS_CC)) {

zend_error(E_COMPILE_ERROR, "Cannot re-assign $this");

}

/* ... ... */

static zend_bool opline_is_fetch_this(const zend_op *opline TSRMLS_DC)

{

if ((opline->opcode == ZEND_FETCH_W) && (opline->op1_type == IS_CONST)

&& (Z_TYPE(CONSTANT(opline->op1.constant)) == IS_STRING)

&& ((opline->extended_value & ZEND_FETCH_STATIC_MEMBER) != ZEND_FETCH_STATIC_MEMBER)

&& (Z_HASH_P(&CONSTANT(opline->op1.constant)) == THIS_HASHVAL)

&& (Z_STRLEN(CONSTANT(opline->op1.constant)) == (sizeof("this")-1))

&& !memcmp(Z_STRVAL(CONSTANT(opline->op1.constant)), "this", sizeof("this"))) {

return 1;

} else {

return 0;

}

}

You can trick that by many ways, though it's useless to do so ;-)

Now how is $this managed ?

When you call a method - which is the only place where you are allowed to use $this - the compiler emits an INIT_METHOD_CALL OPCode.

You can read On PHP function calls or getting into the Zend execution engine about OPCodes for functions.

In the INIT_METHOD_CALL, the engine knows who is calling the method, for $a->foo() : it is $a.

It then fetches $a's value, and memorize it in a global space. Then, it calls the method, issuing a DO_FCALL OPCode. In this OPcode, we fetch back the value memorized (the object calling the method), and we assign it to the internally-global $this pointer : EG(This) :

if (fbc->type == ZEND_USER_FUNCTION || fbc->common.scope) {

should_change_scope = 1;

EX(current_this) = EG(This);

EX(current_scope) = EG(scope);

EX(current_called_scope) = EG(called_scope);

EG(This) = EX(object); /* fetch the object prepared in previous INIT_METHOD opcode and affect it to EG(This) */

EG(scope) = (fbc->type == ZEND_USER_FUNCTION || !EX(object)) ? fbc->common.scope : NULL;

EG(called_scope) = EX(call)->called_scope;

}

Now, when the method is called, if you use $this in its body to affect a variable or call a method, like $this->a = 8, that leads to the ZEND_ASSIGN_OBJ OPCode, that fetches back $this from EG(This).

static zend_always_inline zval **_get_obj_zval_ptr_ptr_unused(TSRMLS_D)

{

if (EXPECTED(EG(This) != NULL)) {

return &EG(This);

} else {

zend_error_noreturn(E_ERROR, "Using $this when not in object context");

return NULL;

}

}

In case you were using $this to issue a method call like $this->foo(), or to pass $this to another function call like $this->foo($this); the engine will try to fetch $this from the current symbol table, like it does for every standard variable.

But this one has been specially prepared, when the current function stack frame has been built :

if (op_array->this_var != -1 && EG(This)) {

Z_ADDREF_P(EG(This));

if (!EG(active_symbol_table)) {

EX_CV(op_array->this_var) = (zval **) EX_CV_NUM(execute_data, op_array->last_var + op_array->this_var);

*EX_CV(op_array->this_var) = EG(This);

} else {

if (zend_hash_add(EG(active_symbol_table), "this", sizeof("this"), &EG(This), sizeof(zval *), (void **) EX_CV_NUM(execute_data, op_array->this_var))==FAILURE) {

Z_DELREF_P(EG(This));

}

}

}

Last thing : the scopes.

When we call a method, the engine changes the scope :

if (fbc->type == ZEND_USER_FUNCTION || fbc->common.scope) {

/* ... ... */

EG(scope) = (fbc->type == ZEND_USER_FUNCTION || !EX(object)) ? fbc->common.scope : NULL;

/* ... ... */

}

EG(scope) is of type zend_class_entry : this is the class the method you ask for belongs to, and this one will be used for whatever object operation you will now perform into the method body; when the engine checks the visibility :

static zend_always_inline int zend_verify_property_access(zend_property_info *property_info, zend_class_entry *ce TSRMLS_DC)

{

switch (property_info->flags & ZEND_ACC_PPP_MASK) {

case ZEND_ACC_PUBLIC:

return 1;

case ZEND_ACC_PROTECTED:

return zend_check_protected(property_info->ce, EG(scope));

case ZEND_ACC_PRIVATE:

if ((ce==EG(scope) || property_info->ce == EG(scope)) && EG(scope)) {

return 1;

} else {

return 0;

}

break;

}

return 0;

}

That's why you can access private members of objects that are not yours, but descendant of your current scope :

class A

{

private $a;

public function foo(A $obj)

{

$this->a = 'foo';

$obj->a = 'bar'; /* yes, this is possible */

}

}

$a = new A;

$b = new A;

$a->foo($b);

This strangeness has lead to many bugs reported by users, but that's the rule in PHP object model : we don't actually define an object based scope, but a class based scope.

So in a class "Foo", you can play with every private of every other eventual "Foo" , not only yourself, like the above example demonstrates.

PHP's object model scope is class based, not object based.

On destructors

Destructors are dangerous. Don't rely on them, because PHP will even not call them in case of fatal errors :

class Foo { public function __destruct() { echo "byebye foo"; } }

$f = new Foo;

thisfunctiondoesntexist();

/* fatal error, function not found, the Foo's destructor is NOT run */

And how about the order the destructors are called, when are they called ?

The rule is clear into the source code :

void shutdown_destructors(TSRMLS_D)

{

zend_try {

int symbols;

do {

symbols = zend_hash_num_elements(&EG(symbol_table));

zend_hash_reverse_apply(&EG(symbol_table), (apply_func_t) zval_call_destructor TSRMLS_CC);

} while (symbols != zend_hash_num_elements(&EG(symbol_table)));

zend_objects_store_call_destructors(&EG(objects_store) TSRMLS_CC);

} zend_catch {

/* if we couldn't destruct cleanly, mark all objects as destructed anyway */

zend_objects_store_mark_destructed(&EG(objects_store) TSRMLS_CC);

} zend_end_try();

}

static int zval_call_destructor(zval **zv TSRMLS_DC)

{

if (Z_TYPE_PP(zv) == IS_OBJECT && Z_REFCOUNT_PP(zv) == 1) {

return ZEND_HASH_APPLY_REMOVE;

} else {

return ZEND_HASH_APPLY_KEEP;

}

}

As you can see, this is a three step destructor calling strategy :

- Loop backwards the global symbol table and call destructors for objects where refcount = 1

- Then loop forward the global symbol table and call destructors for all the other objects (refcount > 1)

- If a problem happens in step 1 or 2, stop calling the remaining destructors

So, that leads to those behaviors :

class Foo { public function __destruct() { var_dump("destroyed Foo"); } }

class Bar { public function __destruct() { var_dump("destroyed Bar"); } }

Case 1 :

$a = new Foo;

$b = new Bar;

"destroyed Bar"

"destroyed Foo"

Case 1 again :

$a = new Bar;

$b = new Foo;

"destroyed Foo"

"destroyed Bar"

Case 2 :

$a = new Bar;

$b = new Foo;

$c = $b; /* increment $b's object refcount */

"destroyed Bar"

"destroyed Foo"

Case 3 :

class Foo { public function __destruct() { var_dump("destroyed Foo"); die();} } /* notice the die() here */

class Bar { public function __destruct() { var_dump("destroyed Bar"); } }

$a = new Foo;

$a2 = $a;

$b = new Bar;

$b2 = $b;

"destroyed Foo"

This procedure has not been randomly chosen. We do things this way, to be extra sure about everything.

You don't like it ? Destroy your own objects by yourself ! This is the only way to master __destruct() calls. If you leave PHP destroy your objects for you, don't come complaining about the procedure that has been matured for years, you always have the choice of destroying yourself your objects, to master the order of destructs (I tell this because here again, we've been filled tons of bug reports about PHP objects destructors beeing called "strangely").

However, in case of any fatal error, PHP will not call any destructor, because a fatal error is likely to have left the Zend Engine in an unstable state, and calling destructors will run user code that may access pointers that are invalid now, and then crash PHP.

We prefer having something stable, and thus we chose not to call destructors in such cases.

In case of fatal error, PHP will not call any destructor

About recursion also : PHP has not many recursion protection. The only ones that exist are about __get() and __set().

If you happen, somewhere in the stack frame of your destructor, to destroy an object of your own : you'll find yourself into an infinite recursion loop that will exaust your process stack size (usually 8Kb, ulimit -s), and crash PHP.

class Foo

{

public function __destruct() { new Foo; } /* you will crash */

}

So, to sum up things in short : do not put critical code into destructors, such as lock mechanism management, because PHP could not call your destructor, or call in an order that's hard to master. If you have critical code in destructors, and rely on them, then manage your objects lifetime by yourself, PHP will call your destructor when your object's refcount falls down to zero, meaning the object is not used anywhere else, and it is safe now to destroy it.

End

Here we are for PHP object model internal design tour. I hope you have a better glance of what happens when you manipulate objects everyday in PHP. Objects are light in term of memory, and their handling is very optimized into the engine. Feel free to use them. Use a well designed autoloader to boost your memory usage, declare your classes in the logical inheritance order, and if you can turn some of the most complex ones into C extensions, you'll be able to optimize many things and increase even more the overall performances of such classes.