PHP strings management

Introduction

Strings management has always been a "problem" to consider when designing a C program. If you think about a tiny self-contained C program, just don't bother with strings, use libc functions, or if you need to support Unicode, use libraries such as ICU.

You may also use libraries such as the well known bstring, the APR strings or even glib strings. Many libraries exist, and once you are a senior C developper, you can easilly build your own library fitting your exact needs.

In C, strings are simple NULL-terminated char arrays, like you know. However, when designing a scripting language such as PHP, the need to manage those strings arises. In management, we think about classical operations, such as concatenation, extension or truncation ; and eventually more advanced concepts, such as special allocation mechanisms, string interning or string compression. Libc answers the easy operations (concat, search, truncate), but complex operations are to be developped by yourself.

Let's see together how strings are implemented into the PHP 5 language core, and the main differences with PHP 7.

The PHP 5 way

In PHP 5, strings don't have their own C structure. Yes I know, that may seem extremely surprising, but that's the case.

We keep playing the traditional way with C NULL-terminated char arrays, also often written as char *.

However, we support what is called "binary strings" , those are strings that can embed the NULL character.

Strings embeding the NULL char can't be directly passed to libc classical functions anymore, but need to be addressed by special functions (that exist in libc as well) taking care of the length of the string.

Hence PHP 5 memorizes the size of the string, together with the string itself (the char *).

Obviously, as PHP doesn't support Unicode natively, the string stores each C ASCII character, and the length stores the number of characters, as we always assume one printable char = one byte : the plain 50-year-old C concept of a "string", ASCII based. If one graphical character (what Unicode calls "Grapheme") were to be stored in more than one byte, then every concept presented here falls down to just being wrong. We always assume that one graphical character equals one byte (no Unicode support). Also, remember that char * buffers can contain any byte, not just only printable characters.

One C char equals one byte. This statement is always true, worldwide, whatever the machine / the platform. When not talking about Unicode but plain ASCII, one char = one printable character.

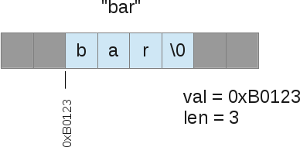

So, we end-up having something like :

typedef union _zvalue_value {

long lval;

double dval;

struct {

char *val; /* C string buffer, NULL terminated */

int len; /* String length : num of ASCII chars */

} str; /* string structure */

HashTable *ht;

zend_object_value obj;

zend_ast *ast;

} zvalue_value;

I lied a little bit when I said PHP doesn't manage strings using its own structure. In fact in PHP 5, a string is used in the str field of the zval (the PHP variable container).

Graphically, this could give :

Problems in the PHP 5 way

This model has several problems, some are addressed in later PHP 5 versions, and others in the new PHP 7 implementation we'll talk about later.

Integer size

First thing is that we store the length of the string into an integer, which is platform dependant.

On LP64 (~Linux/Unix), an integer weights 4 bytes, but on ILP64 (SPARC64), it weights 8 bytes. Things are barely the same for the 32 bits variants. So, depending on your platform, PHP will behave differently and have a different memory image, what you wouldn't really expect. That shows a lack of consistency in supporting several platforms (a crucial concept PHP has always tried to carry) and harden debugging.

Also - this is pretty uncommon I assume - but you can't store in PHP's string a string which is larger than the size of the integer, aka in Linux LP64, you can't have strings which length would be over 2^31, even though your CPU line is 64 bits large.

No uniform structure

Second problem : as soon as we don't use the zval container (and its str field), we end-up beeing forced to duplicate the concept.

As we support binary strings nearly everywhere into the engine, it is not rare in PHP 5, to see again the same kind of structure, but taken out of the zval container.

Examples :

struct _zend_class_entry {

char type;

const char *name; /* C string buffer, NULL terminated */

zend_uint name_length; /* String length : num of ASCII chars */

...

The above code show a snippet of a PHP class internally : a zend_class_entry structure.

As you can see, this latter also got its own definition of a string : a char *name, and a zend_uint name_length that stores the length.

What about hashtables ?

typedef struct _zend_hash_key {

const char *arKey; /* C string buffer, NULL terminated */

uint nKeyLength; /* String length : num of ASCII chars */

ulong h;

} zend_hash_key;

Here again, this zend_hash_key structure is used often when it comes to play with hash tables (very very common use-case) ; and here again, we notice that the concept of "PHP string" is once more duplicated : a const char* arKey and its uint nKeyLength.

Note that in every case, the length is always a typedef that will more-or-less lead to platform integer (zend_uint, uint, int).

Some even being signed, thus dividing by two the size capacity.

So to sum-up this second problem, there is no unified way of representing a string in PHP 5. The concept is always the same : a char* buffer together with its length ; but this concept is not "globally shared and assumed" across all PHP source code, thus many code duplication happens, as well as one last problem.

Memory usage

The last problem is memory consumption.

If PHP meets twice the same string into its life, it will likely store that string twice in memory, or even more than twice.

Add-up every piece of string you can think about, and you'll notice that this is not so little : memory consumption will suffer from the numbers of different copy of the same piece of string in memory.

For example, if two internal layers communicate each other, the top layer passes a string to the bottom layer. If that bottom layer wants to keep the string for itself, to reuse it later for example (with no intention to modify it), well in PHP 5, it has no other way than copying the whole string.

It can't keep the pointer, because the above layer is free to free the pointer whenever it wants to, and also, the bottom layer would like to free that string whenever it wants to, without having the top layer crash in a use-after-free situation.

Just one quick and easy example to illustrate :

static PHP_FUNCTION(session_id)

{

char *name = NULL;

int name_len, argc = ZEND_NUM_ARGS();

if (zend_parse_parameters(argc TSRMLS_CC, "|s", &name, &name_len) == FAILURE) {

return;

}

/* ... ... */

if (name) {

if (PS(id)) {

efree(PS(id));

}

PS(id) = estrndup(name, name_len);

}

}

This is the session_id() PHP function. It is given a string as input (name), and must store it internally in the session module (into PS(id)), to remember and use it later.

This is done by fully duplicating the passed string (the function is estrndup() , this function duplicates a string into memory).

Why duplicate it ? Because if we change the session id again, well, we'll free the last id, but if this last id string were used elsewhere (in your PHP variables), then you will crash reading free'ed memory.

Opposite problem : if we just store the pointer into the session module without duplicating the string it points to, what happens if you - PHP user - destroy the variable this $id was stored in ? We'll end up in the exact same (upside down) situation : Session module is going to use a free()'ed pointer, and then is going to crash.

Those situations, where strings are duplicated just to be kept hot in memory for further usage, happen often in PHP source code. If you dump the heap memory of a PHP process in the middle of its lifetime, you will notice lots of memory bytes that contain the exact same string. This is a pure waste of machine main memory.

To solve this last problem, PHP 5.4 added a well-known-yet-clever concept to the receipe : interned strings.

PHP 7 on its side, reworked in deep the global "string" concept to finally have a very consistent and memory fair solution.

Before PHP 5.4, there were no solution nor consistency regarding the management of strings into memory. This resulted in poor performances, both in term of CPU and memory usage, especially when the web application is big.

Solutions implemented in PHP 5 for strings management

PHP 5 tried to address the memory consumption problem, and managed to find a clever solution to it.

For every other problem related in the last chapter just above, only PHP 7 solves them, because their solution require massive breaks in the PHP source code, and massive code rewrite.

Interned strings

Before PHP 5.4 , every problem related to string management is present.

Starting from PHP 5.4 , the concept of "interned strings" was implemented, and resulted in less memory consumption, thus solving one of the exposed problem (the biggest one in my opinion).

But, as you will see, interned strings require sharing a global buffer, something which is by definition not thread safe.

Thus, at the moment, interned strings are not supported by ZTS PHP.

Interned strings are fully disabled if you run PHP in ZTS mode. You'll then suffer from memory waste in string management compared to non-ZTS.

What are interned strings ?

If you use your prefered search engine with those terms ("strings interning"), you'll land on many pages defining interned strings. That means that we are facing here a general solution, that is implemented in other programming languages, such as Python or Java, and even in BIG stand-alone softwares, such as your favorite IDE, or your favorite video games ( yes, those latter are "just" some BIG C++ softwares ).

Interned strings basically tells that a same string (f.e "bar"); should never be stored more than once in memory, for one process. Easy enough, isn't it ?

But, how did PHP implement this concept, back in PHP 5.4 ?

Let's see that together.

Interning a string is ensuring this string will never be stored in memory more than once per process. For softwares managing big strings, or many strings (like PHP does), this can represent a nice memory saving as well as better performances regarding any string manipulation.

The concept is easy. Whenever we meet a string, instead of creating it with a classical malloc() (we are assuming dynamic strings that can't really be stack allocated), we store the string into a bound buffer and add it to a dictionnary (which is a hashtable). If the string is already present in the dictionnary, the API returns its pointer, effectively preventing us from creating yet another copy of such a string in memory.

However, only persistent strings can be stored in this interned strings buffer, because you know PHP will free the request-bound memory between each request, when we are actually in the process of treating a request, no interned strings must be created as their pointers need to be freed at the end of the request. To accomplish that, we use a snapshot buffer that is reseted to its position at the end of the current request. So interned strings do work for request-scope allocations, but they are less efficient than "persistent" strings that get allocated at PHP startup and reused until PHP dies, because request-allocated interned strings are freed at the end of the current request and thus have a smaller lifecycle.

Here is how we prepare the buffer, at the very early startup stage of PHP (truncated) :

void zend_interned_strings_init(TSRMLS_D)

{

size_t size = 1024 * 1024;

CG(interned_strings_start) = malloc(size);

CG(interned_strings_top) = CG(interned_strings_start);

CG(interned_strings_snapshot_top) = CG(interned_strings_start);

CG(interned_strings_end) = CG(interned_strings_start) + size;

zend_hash_init(&CG(interned_strings), 0, NULL, NULL, 1);

CG(interned_strings).nTableMask = CG(interned_strings).nTableSize - 1;

CG(interned_strings).arBuckets = (Bucket **) pecalloc(CG(interned_strings).nTableSize, sizeof(Bucket *), CG(interned_strings).persistent);

}

What you first must spot, is that the interned string buffer is 1Mb large (1024*1024) and cannot be changed by the PHP user (INI setting). Effectively, when this buffer will be full, it will NOT be resized, and from that point the interned strings API will behave like if there is no interned strings : it will lead us to having malloc()ed our strings.

Now, to create an interned string, we internally use zend_new_interned_string() , and not malloc() or strdup() or anything else :

#define IS_INTERNED(s) \

(((s) >= CG(interned_strings_start)) && ((s) < CG(interned_strings_end)))

static const char *zend_new_interned_string_int(const char *arKey, int nKeyLength, int free_src TSRMLS_DC)

{

ulong h;

uint nIndex;

Bucket *p;

if (IS_INTERNED(arKey)) {

return arKey;

}

h = zend_inline_hash_func(arKey, nKeyLength);

nIndex = h & CG(interned_strings).nTableMask;

p = CG(interned_strings).arBuckets[nIndex];

while (p != NULL) {

if ((p->h == h) && (p->nKeyLength == nKeyLength)) {

if (!memcmp(p->arKey, arKey, nKeyLength)) {

if (free_src) {

efree((void *)arKey);

}

return p->arKey;

}

}

p = p->pNext;

}

/* ... ... */

As you can see, this API immediately returns the string you want to intern, if this latter is already in the interned string buffer.

If not, it will lookup the interned string hashtable to find if the same string is stored into it. This is a heavy operation, as the hashtable needs to be browsed, and the string needs to be per-byte compared. Both operations will likely invalidate your L1 CPU cache, and possibly your L2 cache as well ; but we only create interned strings when this is necessary and will save performances later (heavilly used string). This is a tradeoff between the work needed to create the string (heavy) and the later work done to fetch back this string and use it (light, and memory fair).

If the same string is found in the hashtable, this latter pointer is returned and the original string buffer can also be freed by the API if we asked it to, passing '1' as last parameter.

Let's continue :

if (CG(interned_strings_top) + ZEND_MM_ALIGNED_SIZE(sizeof(Bucket) + nKeyLength) >=

CG(interned_strings_end)) {

/* no memory */

return arKey;

}

Like I said, if the memory buffer for storing the strings is full, the API returns the pointer you passed to it, effectively doing nothing.

Let's end :

p = (Bucket *) CG(interned_strings_top); /* reserve room from our allocated buffer */

CG(interned_strings_top) += ZEND_MM_ALIGNED_SIZE(sizeof(Bucket) + nKeyLength); /* move up the border */

h = zend_inline_hash_func(arKey, nKeyLength);

p->arKey = (char*)(p+1);

memcpy((char*)p->arKey, arKey, nKeyLength); /* copy the string into the interned string buffer */

if (free_src) {

efree((void *)arKey); /* free the original string */

}

p->nKeyLength = nKeyLength;

p->h = h;

p->pData = &p->pDataPtr;

p->pDataPtr = p;

/* ... ... */

return p->arKey; /* return the interned string */

And finally, the string is duplicated (memcpy()) from the pointer you provided (arKey), into the HashTable, which Bucket will be allocated from the interned string buffer itself.

As you can see, there is nothing really complicated, just some clever tricks to make any future manipulation of the related string more efficient.

For example, the string hash (h variable) is computed every time we intern a string. This hash will be needed any time the string is used as a key into a hashtable, and this is very likely to happen, so we prefer eating some more CPU cycles now (by computing the hash), than later at runtime when performances will be critical to the user.

Interning a string is an operation which is done weither when PHP starts, or when it compiles a script, never at execution stage.

Now we must think about string destruction. As you probably understood, interned strings are shared pointers, and thus should never be freed randomly by someone, because any place elsewhere the pointer is used, will lead to a use-after-free bug.

Thus, when we are given a string and want to free it, we must first ask if this latter is interned.

For this, we don't use efree() (the free() equivalent in PHP's source), but str_efree(), which takes care of interned strings.

#define str_efree(s) do { \

if (!IS_INTERNED(s)) { \

efree((char*)s); \

} \

} while (0)

We can see that interned strings are effectively NOT destroyed when asked for (because they are shared and used elsewhere).

Also, if you want to duplicate a string pointer for read-only use purpose, use str_estrdup() , instead of estrdup() (which will duplicate the string in memory in anycase). Look :

#define str_estrndup(str, len) \

(IS_INTERNED(str) ? (str) : estrndup((str), (len)))

Obviously, interned strings refer to shared strings and thus read-only purpose string. Any time you want to modify one of theses strings, for your own usage, you will be required to fully duplicate it in memory and work on your copy. But often, the string is used in a read-only maner, so there should be no need at all to duplicate it in memory if the string is interned (this is the concept).

Interned strings are both shared + read-only concepts, don't attempt to free() an interned string, nor to modify it directly. The main API call

zend_new_interned_string_int()returns a const char* to hint you. If you need to write to the interned string : create a private full copy before, and work on that copy (andefree()it when finished if heap-allocated).

Have you seen how cleverly interned strings are stored into memory ?

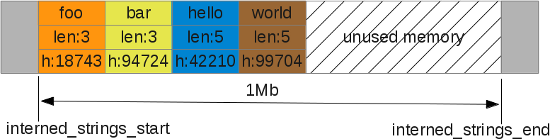

Here is a picture of what the memory layout could look :

Interned strings are stored into a well known bound buffer, so to check if a pointer holds an interned string, we just have to check if its address is inside the interned string buffer bounds :

#define IS_INTERNED(s) \

(((s) >= CG(interned_strings_start)) && ((s) < CG(interned_strings_end)))

This is highly performant, as looking up a HashTable any time we want to know if a string is interned or not, is just a no-go for performance, and would slow down the language a lot, as strings are used everywhere into PHP's heart.

So, how to really free an interned string ? You don't do that as a PHP extension writer. The engine will free the whole interned string buffer at once, once it shuts down (end of PHP life, after having treated several requests) :

void zend_interned_strings_dtor(TSRMLS_D)

{

free(CG(interned_strings).arBuckets);

free(CG(interned_strings_start));

}

This is once more highly optimized, because the buffer is contiguous address, and the free operation will destroy every piece of interned string at once, instead of one free operation per string ( like in PHP < 5.4).

For request-bound interned strings, the border of the string buffer is simply snapshoted when a request is about to come, and restored when the request has gone, thus, every string created between both operations (during a request) will be taken out of the buffer by simply moving the border of this latter (CG(interned_strings_top)).

At the beginning of the request, we snapshot the upper border of the interned strings buffer :

static void zend_interned_strings_snapshot_int(TSRMLS_D)

{

CG(interned_strings_snapshot_top) = CG(interned_strings_top);

}

At the end of the request, we restore it, and delete any reference of the strings from our hashtable:

static void zend_interned_strings_restore_int(TSRMLS_D)

{

Bucket *p;

int i;

CG(interned_strings_top) = CG(interned_strings_snapshot_top);

for (i = 0; i < CG(interned_strings).nTableSize; i++) {

p = CG(interned_strings).arBuckets[i];

while (p && p->arKey > CG(interned_strings_top)) {

CG(interned_strings).nNumOfElements--;

if (p->pListLast != NULL) {

p->pListLast->pListNext = p->pListNext;

} else {

CG(interned_strings).pListHead = p->pListNext;

}

/* ... */

}

}

Now, to have a concrete example of interned strings usage, let's have a look together at the PHP compiler (which allocates request-bound interned strings) :

void zend_do_begin_class_declaration(const znode *class_token, znode *class_name, const znode *parent_class_name TSRMLS_DC)

{

/* ... ... */

new_class_entry = emalloc(sizeof(zend_class_entry));

new_class_entry->type = ZEND_USER_CLASS;

new_class_entry->name = zend_new_interned_string(Z_STRVAL(class_name->u.constant), Z_STRLEN(class_name->u.constant) + 1, 1 TSRMLS_CC);

new_class_entry->name_length = Z_STRLEN(class_name->u.constant);

/* ... ... */

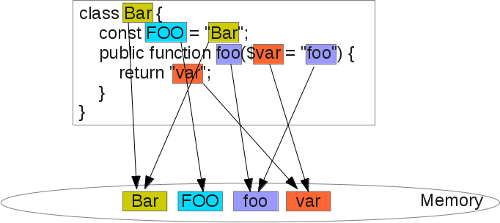

The code above is triggered when PHP compiles a user class, like class Bar { }

Like you can read, the name of the class will be interned, zend_new_interned_string() is used. It is passed a pointer storing the name of the class as it comes from the parser (class_name->u.constant) , and it will return a new pointer to the same string, but interned. Also, the old pointer will be freed and will become invalid (1 is passed as last parameter to zend_new_interned_string(), which means "free the original pointer so that I don't have to do it myself").

If we continue analyzing the compiler, we'll notice that it does the same thing for many concepts : function names, variable names, constant names, userland PHP strings and more advanced concepts, such as OPArray litterals.

Here is what the string-related memory layout of some PHP script could look like :

class Bar {

const FOO = "Bar";

public function foo($var = "foo") {

return "var";

}

}

Each piece of string is effectively stored once and only once in memory, and they are all stored into the same contiguous buffer, and not sparsed everywhere in memory, improving CPU cache efficiency.

Summary of interned strings

Interned strings are a programmatic mechanism designed to store any piece of string (char *) only once in memory. This is a read-only, globally shared concept : one should not change an interned string (usually given as a const char* pointer to prevent that), nor free it.

Also, as the concept involves a global buffer, care should be taken when using a threaded environment. In PHP ZTS, interned strings are simply disabled.

Interned strings have many advantages :

- They save memory - this is their first goal - and the save can be huge on big applications, with tons of functions / classes / variables...

- Interned string hash is computed only once for all and reused when needed (and it is often needed). This saves lots of CPU cycles at PHP runtime.

- Comparing two interned strings ends in comparing two pointers, with no memory scanning at all, which is very performant.

And also drawbacks :

- Creating an interned string often requires scanning a hashtable, and sometimes two string buffers (

memcmp()); this effort must be worth the expected later gains. - Internal developpers must remember that any string could be interned, and thus should never try to free() it directly (will lead to a crash) nor modify it.

- Because the compiler makes use of interned string, it is then slower, but is likely to accelerate your runtime. You must use an OPCode cache solution to fully benefit from interned string advantages.

The OPCache extension for PHP pushes the interned strings concept even further, by sharing the same interned strings buffer accross several PHP process, and by allowing the user to configure the space of the buffer (using an INI setting) whereas traditionnal PHP doesn't allow that.

You can read more about this on the dedicated blog post.

The PHP 7 way

PHP 7 changed many things in the way PHP manipulates strings internally.

Finally a real shared structure and its API

PHP 7 finally centralized the concept of "strings" into PHP, by designing a structure which is used everywhere PHP uses strings :

struct _zend_string {

zend_refcounted_h gc;

zend_ulong h;

size_t len;

char val[1];

};

3 things are noticeable in the structure above :

- The length of the string is stored using a size_t type.

- The real C string is not declared as a char* but as char[1].

- It embeds a refcount : gc

As length are typed on a size_t variable, they weight {platform size} bytes ! Whatever the platform. One of the PHP 5 problems is then solved : under a CPU64, string length will be 8 bytes (64 digits) for every platform (this is one of the definition of the C size_t type).

The string is not stored into a char* but a char[1], this is a C trick called a "struct hack" (look for that term if needed). That allows us to allocate the string buffer together with the zend_string buffer, and save one pointer along having a contiguous area of memory. Performances++

Notice that now, strings embed by default their hash (h). So we compute the hash for a given string only once (usually at compile time), and never after that. In PHP, mainly before interned strings (< 5.4), the same string hash was recomputed every time it is needed, that led to tons of CPU cycles burnt for nothing... Pre-computed hashes have pushed overall PHP performances.

Strings are refcounted ! In PHP 7, strings are refcounted (as well as many other primitive types). That means that interned strings are still relevant, but less : PHP layers can now pass strings from one to the other, as strings are refcounted, we are plainly sure that noone will accidentaly free the string as this latter is still used elsewhere (until doing an error on purpose).

This is the concept behind "reference counting" (search the term if needed) : we now count every place where a string is used (stored), so that it will be freed when nobody uses it anymore.

Let's go back to our session module example. Here is its PHP 5 code recalled to you, followed by its PHP 7 code, just for the part managing strings (what we are looking after) :

/* PHP 5 */

static PHP_FUNCTION(session_id)

{

char *name = NULL;

int name_len, argc = ZEND_NUM_ARGS();

/* ... */

if (name) {

if (PS(id)) {

efree(PS(id));

}

PS(id) = estrndup(name, name_len);

}

}

/* PHP 7 */

static PHP_FUNCTION(session_id)

{

zend_string *name = NULL;

int argc = ZEND_NUM_ARGS();

/* ... */

if (name) {

if (PS(id)) {

zend_string_release(PS(id));

}

PS(id) = zend_string_copy(name);

}

}

Like you can see, we use a zend_string structure in PHP 7, and we use an API : zend_string_release() and zend_string_copy() with it.

static zend_always_inline zend_string *zend_string_copy(zend_string *s)

{

if (!ZSTR_IS_INTERNED(s)) {

GC_REFCOUNT(s)++;

}

return s;

}

static zend_always_inline void zend_string_release(zend_string *s)

{

if (!ZSTR_IS_INTERNED(s)) {

if (--GC_REFCOUNT(s) == 0) {

pefree(s, GC_FLAGS(s) & IS_STR_PERSISTENT);

}

}

}

Just a matter of refcounting : the string is passed from external world to PHP session module, and this latter keeps a reference to the string, never needing to fully copy it in memory, like PHP 5 does.

That is a huge step forward in string management in PHP.

PHP 7 added a real structure and API for string management internally. This is a huge step forward in consistency, memory savings and performances.

If you want to grab the zend_string API, it is inlined (for compilation performance reasons) and stored in zend_string.h.

Interned strings still matter

Like we saw, strings in PHP 7 are now reference counted, and that prevents us from needing to fully duplicate them when wanting to store a "copy" of a string from a layer to the other.

But, interned strings still matter. They are still used in PHP 7, and that works nearly the same way as in PHP 5; except that we don't use a special buffer anymore, because we can flag for gargage collector a zend_string as being interned (the structure now allows us to do so).

So, creating an interned string in PHP 7, is creating a zend_string and flag it with IS_STR_INTERNED

When releasing a zend_string using zend_string_release(), the API checks if the string is interned and just does nothing if it is the case.

The interned strings are destroyed barely the same way as in PHP 5, simply the process in PHP 7 is optimized thanks to new allocation and garbage collection mechanisms.

A heavy migration

You got it ? Replacing any place in PHP source code ( ~750K lines) where we used a char*/int by a zend_string structure and its API ... was not an easy job.

You can see some commit diff that are huge about that.

This could definitely not happen in PHP 5 source codebase, because zend_string simply breaks the ABI, and we don't break the ABI until major versions of PHP.

Migrating PHP extensions is not an easy task neither, zend_string is not the only change in PHP 7, and many big centralized structure have changed significantely in PHP 7. As the ABI is broken between PHP 5 and PHP 7, obviously you'll have to rebuild / redownload your favorite extensions for PHP 7, PHP 5 ones won't load into PHP 7 at all.

Conclusions

You now have a glance on how PHP manages strings into its heart. Most of the strings come from the PHP compiler: the user PHP scripts. PHP 5, starting with 5.4, introduced interned strings, which is a concept meaning to save memory by not duplicating strings into memory. Before PHP 5.4, string management was plainly missing in PHP.

Starting with PHP 7, PHP added a new structure and a nice reference-counting-based API for string management, resulting in even more memory savings, and nice consistency accross the language.